Music and Musicians / Musica e musicisti

Prepared by Richard Kitson and Elvidio Surian

Online only (2021)

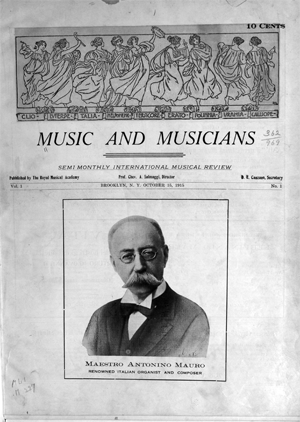

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries various emigrant populations—German, Polish, Czech, Russian among the many—were ranked by popular opinion in the United States according to the level of education and culture attained by its individuals. The highest rank often belonged to the Germans, understood in the United States to be the masters of things musical. In general, Italian immigrants were ranked amongst the lowest, owing to a lack of education, and difficulties encountered with a new language, English, and the notorious criminal activities of the Italian “Mob.” Little of the centuries of Italian cultural wealth in many fields was known and appreciated in the new country. In the realm of music, in particular, German music was placed in first rank. The Italian-American music journal, Music and Musicians / Musica e Musicisti [MEM], was created to rectify this erroneous and negative opinion. Like many journals of this period the content consists of biographical sketches of composers and singers, reviews of opera performances and concerts, reviews of music publications and books on music and considerable discussion of the wrongs brought against Italian music and Italian musical life.

Each issue of this publication is organized in two parts, the first written in English and the second in Italian, both parts giving comprehensive explanations and reviews of Italian composers and performers of Italian music, as well as discussion of the musical life of Italian-Americans in New York City and its environs (New York State, Connecticut, New Jersey and Pennsylvania). In Music and Musicians, each of the English- and Italian-language parts receives one half of each thirty-two-page issue. The English portion of this journal, titled Music and Musicians: International Musical Review, is somewhat general in content, while the Italian portion, given under the title Musica e musicisti, revista mensile di arte, musica e letteratura [Music and Musicians, monthly review of art, music and literature] deals more extensively with Italians and Italian music in New York City and in Italy. The editor, Alfredo Salmaggi, proclaims the journal to be the “Unica pubblicazione musicale italiana negli Stati Uniti” [Unique Italian music publication in the United States] with “circulation over 15,000 copies.” The writings of Salmaggi and other educated Italian Americans, the principal features of most issues, deal with a wide-ranging number of musical topics. Salmaggi was well-known among the Italian musicians active in the United States at this time. His accomplishments included activity as impresario of a number of Italian travelling opera companies, teaching and performing.

Many American journals of this period show the influence of English and/or German music journals in matters of organization and content. The appearance of this and another Italian-American periodical, International Music and Drama, differently organized and not particularly dependent on outside sources for their main materials, requires some explanation. The rationale for publication of predominately Italian music interests is expressed by the editors of both journals. In his first issue of Music and Musicians, Alfredo Salmaggi articulates the problem and uses an openly hostile manner toward German musical interests in his writings. In an editorial entitled “The Passing of German Music,” Salmaggi describes “the complete failure of the monstrous dream of German hegemony,” gives a fair retrospective of the highest pinnacles of German music, discusses the dominance of Wagner’s art in the late nineteenth century, and relates these achievements to the awakening of composers in the countries surrounding Germany. Salmaggi offers a discussion of a German operatic music that attempts to rival Italian operatic music which had formerly held “complete sway over the world,” and then claims that German music is now in a state of decadence following Wagner’s triumph. Salmaggi believes that the resurgence of Italian music, after years of lethargy, could now to be achieved by contemporary Italian composers of operatic music‒Puccini, Pietro Mascagni, Umberto Giordano, Italo Montemezzi‒and with the growth of Italian instrumental music by Illdebrando Pizzetti, G. Francesco Malipiero and Vincenzo Davico among others.

The central issue of this New York music journal is the performances of Italian opera by the many opera companies, large and small, in many parts of the United States. Foremost are the seasons at the Metropolitan Opera House under the direction of the noted Italian general manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza, formerly director of the Teatro alla scala in Milan. Considered by the journal to be the most important events of the New York musical season, performances are reviewed extensively in the both the English- and Italian-language sections. The August, September and October issues feature announcements and biographical information about the composers, singers and the conductors and overviews of the forthcoming Metropolitan Opera Company repertory. All these musicians are represented in numerous photographs showing performers both in costume and street clothes and in caricature. This was an age of remarkable Italian singers and musicians active in the Italian and French wings of the Metropolitan Opera House: Italian tenors Enrico Caruso, Giovanni Martinelli, Beniamino Gigli, Lucca Botta and baritones Pasquale Amato, Giuseppe De Luca and Antonio Scotti, the bass Virgilio Lazzari, the Italian sopranos Amelita Galli-Curci and Claudia Muzio and the Spaniards Lucrezia Bori and Maria Barrientos and the New Zealander, Frances Alda. Noteworthy are reviews dealing with the emergence of the Italian-American soprano Rosa Ponselle, first as a student of an Italian vocal professor and then professionally in Verdi’s La forza del destino at the Metropolitan Opera House. The glamorous American soprano, Geraldine Farrar, active in Italian and French operas and in opera films for the developing motion picture industry, receives great attention. Of importance are the achievements and haughty behavior of Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini, and the Italian conductors Gennaro Papi and Giorgio Polacco, who assisted the Toscanini in the preparation of operas at the Metropolitan Opera House and then assumed conducting responsibilities during the maestro’s absences. All represents an enormous effort to shore up opinions about Italian music and musicians.

Each week of the Metropolitan Opera Company’s performances are critically examined in the journal. Gatti-Casazza himself makes remarks about the intense activity required for a repertory of twenty-three operas in a season of twenty-three weeks. This repertory consists mainly of Italian operas by Donizetti, Bellini, Verdi and Puccini and French operas by Massenet, Bizet and Saint-Saëns (sung in the Italian language). New Italian operas by Umberto Giordano (Mme Sans-Gêne), Italo Montemezzi (L’amore dei tre re) and Pietro Mascagni (Iris), all rarely performed today, were in their time hotly disputed as both successes and failures. The problems of Mascagni’s operas following the enormous success of Cavalleria rusticana receive extensive discussion, in particular with reference to the disputes about ownership between the Ricordi and Sonzogno publishing houses. Novelties included Russian operas Borodin’s Prince Igor; and Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, both sung in Italian by a number of Italian singers. The distribution of the vast public within the Metropolitan Opera’s auditorium begs discussion that reveals the high bourgeois of the banks and industries in boxes, expressionless and generally dozing; the connoisseurs in the upper balconies; the true music lovers (many Italian) standing or squeezed into the galleries. A wretched adjunct of this operatic world, the notorious “claque,” active at the Metropolitan Opera House, is examined with apparent disgust.

Hostility toward German and Austrian music and toward the German military’s actions against Italian and other nations’ singers and instrumentalists is a major topic throughout the years of the World War. Crossing the Atlantic Ocean became a serious problem that limited both European and American singers and instrumentalists from fulfilling contracts for operatic and concert appearances in the United States, or from returning to Europe at the American music season’s conclusion, and then returning westward for the beginning of the following American season. Outcries deride the cold-blooded, premeditated assassination of peaceful citizens and defenseless women and children travelling on the steamships Ancona and Lusitania, both sunk by German U-boats in the cold waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Prominent among the many of such tragedies is the death of Spanish composer Enrique Granados, who, returning to Europe after leading performances of his opera Goyescas at the Metropolitan Opera House became victim of the sinking of the aforementioned passenger steamer “Ancona.” Owing to the publication of troubles engendered by the war between American immigrants of different origins, Walter Damrosch’s advice “It is well to remember we are Americans no matter where we are born” is reprinted.

Alfredo Salmaggi follows the progress of the hostilities and the effects on the music making in the United States. He gives accounts of the effect of war on musicians. For example, British born pianist and composer Eugene D’Albert’s expulsion from membership in the Imperial Association of German Composers because of his original British nationality; pianist Leopold Godowsky’s opinion that “much of German music sets forth German life and aspirations in such a way as to beguile the hearer and entrap the unwary.” Reports of the damage created by the war are numerous, varied and sometimes ridiculous: the lack of Italian singers brought about the cancellation of an opera season in San Francisco; Italian composer Ruggiero Leoncavallo’s refusal to join the Italian Artists’ League’s protest against Germany is reported to the composer’s detriment; a reprint from the London Saturday Review finds Prussian self-assertiveness in Richard Strauss’s symphonic poem Ein Heldenleben; universal animadversion against Teutonic high-handedness results in gradual reduction in the number of German opera performances at the Metropolitan Opera House. The return to Italy of the Italian singers and all secondary and accessory personnel employed at the Metropolitan Opera House is discussed. Dutch tenor Jacques Urlus and Czech soprano Emmy Destinn, both important singers at the Metropolitan Opera House, are praised as American householders who remained in America despite the war. The war and its effect on the American stage results in reports that spectators were perplexed by the flood of sex plays in dramatic theatres. This situation led to an inquiry on the cause of this deluge of adulterated facts, coupled with “loquacious vulgarities and tawdry display of unmentionable vices.” Resistance of the public towards Wagner’s Die Götterdämmerung and Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier are revealed in the drastic reduction of ticket sales for these operas at the Metropolitan Opera House.

Several Italian-American organizations for the promotion of Italian musical art were created with the support of MEM and other music journals. Prominent among such institutions is the Italian Musical League. An article, part of the well-known column “Mephisto’s Musings,” printed in the May 1918 issue of Musical America, is subtitled “The Boches’ Attack on the Italian Musical League” and puts forth the claim that the new organization acts in opposition to the “Musical Alliance” of John Christian Freund, founder and editor of the Musical America and a staunch admirer of German music. This problem did not subside, for in the next issue of Music and Musicians Salmaggi features an article headed “Boches are still mighty powerful in America!” and puts forth the opinion that the assault on the Italian Musical League in Musical America was written, edited and read by Germans and descendants of Germans and Germanophiles. In the article “How Mephisto retracts his calumnies,” Musical America’s editor Freund begs forgiveness, but utters more anti-Italian venom. In his next issue, Salmaggi deals with the author of the column “Mephisto’s Musings” and his reaction to critical articles in Music and Musicians. Another Salmaggi article entitled “Why Is Not America More Severe with the ‘Boches,’” is an inquiry about the support of important German propagandist personages active in the United States. German incidental music, led by German musicians at many New York theatres, receives an outcry against the employment of “enemy musicians performing enemy music.” With the conclusion of the First World War fierce discussion of the relative merits of Italian and German music subsided and the Italian-American music journals faded into relative oblivion.

This RIPM index was produced from copies of the journal held by the New York Public Library, Library for the Performing Arts (Lincoln Center) and the Library of Congress. Unfortunately, a full run could not be reassembled from existing copies of the journal; many issues appear to be lost. If the missing issues should come to light in the future, these shall be added to this RIPM publication.